Some say what your kids are taught may be different than what kids are taught in other school districts. One of the reasons why is because each school district chooses what educational resources, like textbooks, are used, but there are learning standards set by the state.

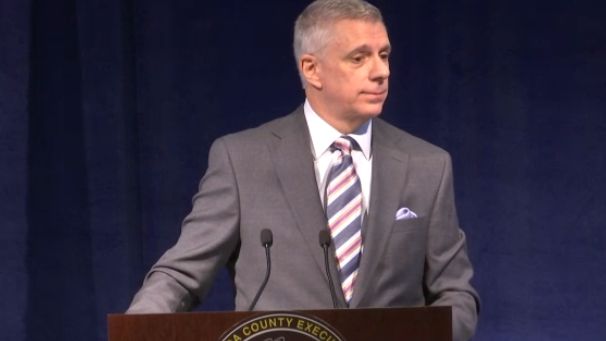

"For example, New York could be all educators. Whereas in Texas, it could be educators, religious officials, political officials in the mix. That's generally the case. In some ways, it mirrors the news. People are choosing textbooks like news, that fits what they want to hear or read," said Utica College distinguished professor of East Asian history David Wittner.

Wittner is talking about the groups of people who review textbooks.

As we previously discussed in the first "What Will History Remember?" story, changes in location can translate to changes of values or perceptions, leaving room for bias.

But no matter how objective a writer is, an issue, maybe one impossible to fix, remains.

"The issue with any textbook is, there's an awful lot of history," Wittner said. "You can't put it all in. So you have to choose, and the question is what you're choosing and how you interpret what's being chosen to put in there."

History affects how we see things; what we know or don't know can shape our perceptions.

A few years ago, the village of Whitesboro's seal depicted what locals describe as a "friendly wrestling match" between the village's founder and a Native American, faced national scrutiny.

Some people were angry saying it was "racist," others mocked the village, while locals tried to educate people of the seal's story.

Dana Nimey-Olney, the village's historian, was the village clerk at the time.

"It was scary at times," she said. "A lot of hate mail, a lot of nasty phone messages. We had mail that was stopped at the post office in Syracuse by the postmaster because they were afraid it had something in it."

In the end, the seal was changed but the question remains: if people knew the seal's story, could some of the outrage have been spared or traded for civil conversations?

"It's hurtful that it would go out in national media that this village, that this town would have anything negative or hurtful or mean-spirited. It just doesn't fit with our community," Nimey-Olney said.

This example is on a local level, but Colgate University political science professor Nina Moore says what is taught about our country's story can shape how we see large-scale issues.

"If we're trying to understand the development, the evolution of the country, then we should be part of a national conversation in deciding what gets focused on, what the facts and events are that help to make out that focus, and then the interpretation of those facts," said Moore.